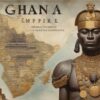

The Rise and Fall of the Ghana Empire: Africa’s First Great Kingdom

Long before the rise of Mali or Songhai, the Western Sudan was home to a powerful and prosperous civilization—the Ghana Empire. Often referred to by Arab writers as the “Land of Gold,” Ghana was the first of the great West African empires, thriving between 300 AD and 1240 AD. Its rich legacy of trade, political organization, and military dominance laid the foundation for successive empires and remains a landmark in African history.

The Origins of the Ghana Empire

The Ghana Empire called the Wagadou (or Wagadu) Empire by its rulers, was located in what is today southeastern Mauritania, western Mali, and parts of Senegal. It was inhabited primarily by the Soninke people, who were part of the larger Mande-speaking group.

While some early historians speculated that Ghana was founded by outsiders from North Africa, most credible scholarship attributes its origins to indigenous Soninke rulers. These people established a kingdom that was already flourishing by the 8th century and later came to be known by the royal title, “Ghana,” meaning “warrior king.”

Strategic Location and Trade

Ghana’s rise was largely due to its strategic position between the Sahara Desert and the savannahs. It served as an essential link in the trans-Saharan caravan trade, acting as an entrepôt—a hub where traders from North Africa and sub-Saharan regions exchanged goods.

Key trading commodities included:

- Gold from Wangara (Bambuk region)

- Salt from Taghaza

- Copper, ivory, beads, ostrich feathers, and slaves

Ghana’s capital, Kumbi Saleh, became a bustling commercial center, attracting merchants from across the continent and beyond. The introduction of the camel, the so-called “ship of the desert,” around the 7th century significantly increased the volume and reach of this trade.

Ruins of Kumbi Saleh, ancient capital of the Ghanaian Empire (Image by https://i0.wp.com/www.socialup.it)

The Silent Barter System

One of the most fascinating aspects of Ghana’s trade was the “silent barter” system. This method allowed traders—particularly those who didn’t speak the same language—to conduct business without direct communication. Goods were left at designated locations; the second party would then offer items of equivalent value. If both parties agreed, the exchange was silently completed.

This system enabled Ghana to maintain control over trade, protect its gold sources, and foster trust among diverse trading groups.

Wealth and Revenue Generation

Ghana’s rulers grew immensely wealthy through:

- Taxes on imports and exports (e.g., one gold dinar per donkey load of salt entering the empire)

- Monopolizing the gold trade

- Tributes from vassal states

- Spoils of war

- Court fines and judicial penalties

The king of Ghana was known as the “Kaya Maghan” (King of Gold) and was regarded as both a spiritual and political leader.

A Powerful Government Structure

Ghana’s government was a monarchy supported by a Council of Ministers, akin to a modern-day cabinet. Key figures included:

- The Vizier (Prime Minister)

- The Interpreter, who facilitated communication with locals and foreign dignitaries

By the 11th century, many of these officials were Muslims, which helped Ghana interact effectively with Arab traders and diplomats.

The empire was divided into:

- Central Ghana – ruled directly by the king

- Provincial Ghana – vassal states allowed relative autonomy but required to pay tribute and supply soldiers when needed

Expansion Through Military Might

Ghana’s ambition to dominate trade routes led to military conquests. At its peak in the 10th century, the empire encompassed Hodh, Tagant, Ankar, Bagara, and stretched from the Niger River to the Senegal River.

Ghana’s army reportedly had 200,000 soldiers, including cavalry units. Its military superiority stemmed from:

- Horse-mounted troops

- Iron weaponry (spears, swords, arrowheads)

- Poison-tipped arrows

These advantages helped Ghana conquer trade hubs and maintain internal control.

Administration of Justice

The king of Ghana served as the supreme judge, hearing cases and appeals. Local disputes were first addressed by village heads, then escalated to provincial governors, and finally to the king, if necessary.

This multi-tiered justice system, combined with written records and rapid communication via horses, contributed to efficient governance.

Decline and Fall of the Empire

Despite its strengths, Ghana eventually fell due to internal weaknesses and external threats:

Internal Issues:

- Difficulty managing the vast empire

- Lack of political unity among diverse subjects

- Dependence on a massive military to enforce loyalty

- Growing autonomy and rebellion among tributary states

External Factors:

The Almoravids, a fanatical Muslim Berber group, launched a jihad to reclaim control over the trade routes and spread Islam by force. In 1076, they captured Kumbi Saleh, compelling many Soninke to either flee or convert to Islam.

The aftermath:

- Tributary states seceded

- Trade was disrupted

- Agriculture declined

- Ghana’s power and economy crumbled

Though the Soninke briefly regained independence in the 12th century, they never restored the empire’s former glory. By the end of the 13th century, Ghana had been reduced to a shell of its former self.

A painting depicting Tunka Manin

The Ghana Empire was a pioneer of African statecraft, setting an example in economic management, political administration, and cross-cultural diplomacy. Its control of the gold-salt trade not only brought great wealth but also connected sub-Saharan Africa to the wider Islamic and Mediterranean worlds.

Though it fell, Ghana’s legacy lived on—passed to the Mali Empire and later the Songhai Empire, each drawing inspiration from Ghana’s achievements. In modern times, Ghana’s name was adopted by the newly independent nation in 1957 as a tribute to this powerful and prosperous African civilization.